- Home

- De Silva, Diego

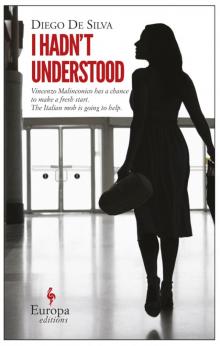

I Hadn't Understood (9781609458980) Page 8

I Hadn't Understood (9781609458980) Read online

Page 8

“I’m here,” I say, enunciating, ready for a fight. And in fact, he immediately becomes all tractable, paper hoodlum that he is.

“I didn’t hear you say anything.”

“I was thinking.”

“Ah.”

“Listen, bear with me, colleague,” I ask naïvely, “but if Fantasia already had a lawyer, namely you, why didn’t he call you to be present at his judicial interrogation?”

A meditative pause ensues.

“Oh, he called me,” he replies, sighing as if I’d put my thumb on a sore spot, “it’s just that I had my cell phone turned off that day.”

Whereupon it dawns on me that the best thing to do now is to change the subject.

“So tell me something,” I say, “what’s all this about the dog?”

“Wait, you mean you don’t know?”

“Well, you hear me asking.”

“Excuse me, but haven’t you read the file?”

I look like an asshole.

“No. That is, yes. I mean, I just wanted you to explain a few details.”

He replies with telegraphic haughtiness. This time, though, I don’t react, considering my misstep.

“The hand. In the backyard. Was put there. By the dog. Fantasia’s dog. A pit bull. Ringo.”

“Okay. Good. Now we have a name and a breed. Then what?”

“Then nothing, he took it and buried it in the garden. You know how animals do when they’re on the hunt, and afterward they conceal their prey? The dog hid it right there, behind the garage. The Carabinieri show up, find the hand, and fasten up the cuffs. In the same hole, they found the dog’s tags, with name and address. Ringo must have lost it while he was digging.”

“Ah,” I marvel, as I organize, then and there, an imaginary projection of the scene, with the pit bull sneaking furtively into Burzone’s specially equipped autopsy room in the garage behind his detached villa, it sees the sections of cadaver spread out on the operating table, yelps in excitement, doesn’t even stop to think, snatches the hand, and scampers out the door, all unbeknownst to Burzone, who had probably stepped away for some unexpected urgent errand (I don’t know, to make a call on his cell phone and the reception under the stairs was no good, or else just to pee, maybe). Then I imagine Burzone coming back, counting up the limbs, and coming up one short. I have to stifle a laugh.

I can just picture him, furious, stepping out into the garden and searching Ringo’s doghouse; the pit bull, off to one side, watches him with his ears lowered, fearing an imminent beating; Burzone fails to find the loot in the doghouse, wanders the immediately surrounding area in an unsuccessful search, and so he moves on to Plan B: he seizes the animal by the collar and interrogates it, Talk, you bastard, tell me where you put it; Ringo takes the beating but doesn’t spill the beans (“I don’t know what you’re talking about,” his mournful doggy eyes seem to say); Burzone loses his temper and starts flailing clumsily away at the dog; the pit bull takes it like a worn-out boxer but never quite understands what the hell its master wants from him, and it howls brokenhearted out of a general sense of guilt. At that point, I can’t help it any longer, and I break out in a nasal burst of laughter.

“Oh,” the disinterested colleague calls.

“Eh,” I reply, wiping a tear away from the corner of my right eye.

“What are you doing, laughing?”

“A little, yes, truth be told.”

“I don’t see anything to laugh about. And neither does Fantasia, I’m willing to bet.”

Okay, this is when I spit right in this guy’s face, I tell myself. And I’d be on the verge of losing my temper, for real, if it weren’t for the fact that it all just strikes me as so ridiculous.

“So, what? You want to tell him about it?” I say.

“Oh, now, really,” he replies, with the unmistakable sound of his tail tucking between his legs.

We sit in silence for a while.

I think back to the trailer I just watched. I still feel like laughing, but this time I manage to control myself.

“So what do you want to do?” he asks me.

“What do I want to do about what?”

“About Fantasia—what do you mean what?”

Oh, here we are. The poor man finally gets to the point.

“So, you’re asking if I’ll accept the appointment?”

He says nothing, opting for silence as assent. So I let him dangle uncomfortably for a while, like in the elimination scenes on Big Brother, when the contestants slump in their chairs waiting for the presenter in the studio to drop the axe. And in the quagmire of seconds that follow, I realize that the news of Burzone’s appointment is making me disgustingly happy. I’m ashamed to admit it, but I still feel gratified by this fiduciary appointment.

“I don’t know,” I reply, taking my own sweet time. “I’ll have to think it over.”

“Ah,” he says.

“You know, I have so many obligations these days,” I add, shivering at the sheer fabrication.

A moment of silence, after which my rival drives home a lunge that I really wasn’t expecting.

“I can imagine how much work you have.”

I undergo a wave of menopausal heat, culminating in an instantaneous suntan.

Okay, I’m not a particularly well-known name among the denizens of the justice system. I don’t represent banks, insurance companies, businessmen, public administrators, Camorristi, or wealthy citizens (in fact, you might reasonably wonder: “So what is it exactly that you do for a living, if I may ask?”). I don’t frequent high-society occasions, I don’t play tennis with magistrates. I share the rent on a group office. I have no secretary, I have no paralegals or interns. Most of the time that I ought to be devoting to work (which I don’t have) I spend inventing occupations that resemble work (like walking up and down the hallways of the courtroom with nothing to do, sticking my head into the hearing rooms to watch other lawyers argue cases, making Xeroxes that I don’t need, spending anywhere from a scanty half-hour to an entire hour in the library, pretending to be absorbed in legal research, and other palliatives of the sort). I’ve got sixteen years of professional activity under my belt, and I file tax returns that are frankly embarrassing. I’m afraid I’m going to be audited one of these days, but even though the numbers on my returns look highly implausible, they are the plain truth. And the Italian tax authorities, it’s well known, make a fundamental presumption of falsehood; in fact the burden of proof is reversed in tax cases.

But that doesn’t mean you can crack funny. Especially not when you’re the one who called me out of fear that I’d snatch the client off your plate, for that matter.

“Well, you know what I say?” I reply, flaring my nostrils. “Now that I’ve had a chance to think it over, it’s a case that intrigues me. I think I’ll take it.”

The wretch says nothing.

“Well, all right then, listen,” he says resignedly after a while. “We should probably meet to plan out our strategy.”

I consider the proposal.

“Actually, the first thing I need to do is go see Fantasia.”

Pause.

“There’s no need for that, you can talk to me.”

I stare intensely at the Edward Hopper poster on the facing wall as if it could understand me. I step into it, I have a sudden thirst for a beer. I sit down alongside the other late-night customers there at Phillie’s bar, I rest an elbow on the counter. The girl in red doesn’t even dignify me with a glance.

Does this guy take me for a complete idiot?

“Excuse me, can I ask you a question?” I ask.

“Of course.”

“Is this phone call your idea, or did Fantasia tell you to call me?”

He stalls for time, hamster that he is.

“Are you there, Counselor . . . ?” I ask, enunciating carefully.

“Picciafuoco. Nino Picciafuoco.”

Oh, right, James Bond in person.

“Did you hear the question

, Counselor Picciafuoco?”

Another guilty pause.

“Yes. No. Well, anyway, don’t worry about it.”

“Don’t worry about what?”

Now he’s treading water.

“No, I was just saying there was no need, because anyway I’m very well acquainted with Fantasia’s situation, and after all, as you can imagine, I’ve been his lawyer for years, all I was asking was if you accept, and if so, we can work out terms, it was mainly just to spare you the time and the bother of going all the way out to the prison to talk with Fantasia, that’s all.”

I let a few seconds go by.

“Well, yes, in fact, I do have a lot of work. But not so much that I can’t take the time to meet a client who’s asking me to take on his defense.”

“Ah,” he says.

It sounds like: “Ah, how painful!”

“Anyway, thanks for calling,” I cut the conversation short.

“Sure. My pleasure. No. Shall we talk again?”

“If we have something to talk about.”

He hesitates. He says nothing.

And then we hang up.

I interlace the fingers of both hands, cradling the back of my head, while I lean against the backrest of my Skruvsta and review the situation. I have no intention of defending that corpsemonger Burzone, but I am enjoying the idea that Picciafuoco thinks I will.

I take a deep breath and smile, but my sense of satisfaction begins to crumble almost immediately. Like a seismic tremor stirring beneath my thoughts, a sneaking suspicion becomes increasingly credible as I manage to get it into focus. Like one of those faint, distant earthquakes that you’re not even sure you heard, but your eyes go straight up to the chandelier.

What an idiot you are, I say to myself, are you thinking of turning down the appointment? Who do you think you are, Alfredo De Marsico?

No, it’s precisely because I don’t think that I’m Alfredo De Marsico that I don’t want to take the case, I weakly retort.

What a lovely answer, I tell myself. What should I do, just admit you’re right, and we can close the debate right now?

I lower my head.

Ah, okay. Let’s see, maybe we should try to sum up: first of all, it’s not clear why you should do Picciafuoco this favor (did you hear him say, “I can imagine how much work you have”? I felt like slamming the phone down, right in his face), so he can go around telling everyone that you lacked the balls for the job, so you turned it down; second, for years you’ve been scraping by with fenderbenders, small-claims court, contracts and leases between relatives, leaks and water damage in apartments, insults and quarrels and condominium boards. For once in your life a real case comes along, and what do you do? You turn up your nose?

He’s a butcher, I try pointing out. For the Camorra.

So what? I say to myself. What are we turning this into now, a moral question?

Well, yeah, in fact, I venture.

Oh, I see, I say to myself, all of that nonsense you never get tired of spouting about the right to legal counsel and how even the worst murderer has a right to a defense lawyer who will argue his case, if for no other reason than to make it possible to have a trial, because otherwise the alternative is to go back to the Inquisition, and so on—that was all bullshit? Ah? Funny that you should happen to come to that realization now, isn’t it?

I’m afraid, I whine.

I know, I say to myself.

I don’t want to, I add.

You have to, I say to myself.

I don’t know the first thing about criminal law.

Oh yes you do, I say to myself.

Oh no I don’t, I insist.

That’s not entirely true, I say to myself.

Yes it is, I reply.

But you wrote your thesis about criminal law, I say to myself.

Eighteen years ago, I respond.

About pornography, I say to myself.

I was just interested in the subject, I answer.

Ha, ha, I say to myself.

Eh. Ha, ha, I say back to myself.

You did pretty well for yourself at Burzone’s hearing, I tell myself.

Dumb luck.

Are you sure of that?

How the hell do I know?

I find them debilitating, these face-to-face confrontations with myself. Especially when I’m on the losing side of the argument.

The phone again.

Unknown caller. Okay, let’s answer and see who it is.

“Counselor Malinconico?”

A woman’s voice. Fairly young. I’d say barely thirty. Making a distinct effort to shed her dialect. Vowel formation reminiscent of a suppository. By the time she’s said a couple of sentences I ought to be able to guess her hometown.

“Yes, this is he,” I confirm.

“Buon giorno, Counselor Malinconico, this is Signora Fantasia speaking, am I interrupting something?”

I can’t believe my ears: the First Lady herself. I’m on the verge of getting to my feet.

“No, not at all. Please go ahead.”

“I need to speak with you urgently, Counselor Malinconico. It’s about my husband, Domenicu Fantasia, you represented him just a few days ago.”

By this point I’d be willing to stake five hundred euros on Lady Burzone’s birthplace. It’s a town where not long ago two entire families reciprocally rubbed one another out in broad daylight, over some trival disagreement, as it happens. Like two third cousins (once removed) had a shouting match, followed by a fistfight in the town square over some bitch who dated them both, fully aware of the havoc it would unleash. One of them went home with a fractured septum whining that his cousin had had an easy time of it because he was so much bigger. Whereupon his father said: “Oh, no, this is a problem between you kids, I’m not getting involved.” And the cousin with the fractured septum grabs his car keys, goes downstairs, and a few minutes later he’s run over his distant cousin in the middle of the town square. At this point, one of the uncles of the guy under the car had been watching it all from his balcony, and now he wades into the melee with a handgun. To make a long story short, it culminates in bloody tragedy. So brutal that, at first, the detectives figured that this must be someone settling scores with someone else who’s trying to elbow in on the profits from some local crime ring or bid-rigging (it later emerged that the two parties to the dispute belonged to rival crime clans). That theory was bolstered by the revealing detail of the bedroom slippers on the feet of one of the corpses (this was the uncle who’d watched from the balcony as his nephew was run over on the piazza), a clue that immediately suggested the old technique of an urgent family appointment, a favorite when close relatives are the targets slated for elimination (basically, the victim is hustled outside so fast that he never even has time to put on a pair of decent street shoes; in fact, the corpse is found just a few yards from the front door).

“Ah, well of course, how could I forget,” I answer, pretending to emerge from great concentration.

“When could I come see you, Counselor Malinconico?”

I leaf noisily through my half-empty appointment book.

“Well, let’s see . . . would Thursday at 5 P.M. work for you?”

“Well, if it’s possible, I’d prefer something sooner, Counselor Malinconico.”

I don’t know why it is, but whenever someone says my name too often, I feel like looking around. As if someone else were about to show up. I don’t know if I make myself clear.

“Ah,” I say. “Well, let’s see. Just a moment . . . Tuesday at 3:30?”

“Well, actually, I could come today, if it’s not a problem.”

“Today? Today when?” I answer, aghast.

“Right now, Counselor Malinconico.”

“But, really, you catch me at a disadvantage, madam. I have an appointment at 5:30 and . . .”

“I’m downstairs, outside your front door, Counselor Malinconico. I could come straight upstairs, if you’d be so kind as to see me right now.

”

I exhale, outwitted.

“Well, all right, come up right now, what can I say?”

We say goodbye.

Here’s another distinguishing feature of the members of the Burzone club: there is no way to get them onto a waiting list. They ignore the concept of yielding the right of way, of waiting for their turn. They are past masters when it comes to breaking elementary rules. With their well-controlled obsequiousness, with their insistent good manners, the way they mention your name in every sentence they utter, in fact they’re telling you: “Look, you might as well do what I’m asking you, because there is no way I’m leaving until you do.” In other words, they’re laying it down in such a manner that you’re the one who suggests making an exception in their case, just to get them the hell out of your hair. They make you abandon your principles. Because a principle is theoretical, while nagging insistence is all too real.

Anyway, to come back to the issue of hearing yourself called by your name every time, I’m pretty convinced that, in criminal terms, a constant evocation by name is an investiture. The procurement of a contract. Close parenthesis.

In order to rid myself of the creepy sense of personal compromise that comes with having submitted to her demand, I organize then and there a modicum of set design for the imminent arrival of Her Pushiness: I carefully conceal the Innocenti steel pipe behind the Kvadrant curtains, I grab a few random files from the Billy glass bookcase and spread them out illogically on the Jonas desk, I break open a volume of the civil code and another hefty tome of criminal procedure (the latter book with at least half its leaves still uncut, not exactly fresh from the bindery), and I slap them on the desk facedown, pages open, one near the phone and the other next to the Dokument letter tray. The next step is to pull my jacket off the Radar coatrack and put it on, then I unzip my trousers, retuck my shirt tails, zip back up, arrange the two Hampus chairs in a symmetrical array, and finish up with a quick glance at the Bonett mirror, where I inspect myself, giving myself a searching scrutiny as if I owed myself a sizable sum of money, in order to impose a minimum of juridical seriousness on my features. Just then, I find myself wondering what strange mechanism makes it seem so natural to people to make an angry face when they want to appear attractive; but I’m too late to give myself an answer because the sound of the doorbell breaks in, overwhelmed in real time by the yelping of the goddamned toy spitz.

I Hadn't Understood (9781609458980)

I Hadn't Understood (9781609458980)